Where it started

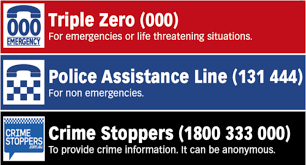

Sitting at my desk at work in the inner-city suburb of Paddington, Sydney I continue to take call after call from people who may just be experiencing the most traumatic event in their life. Thousands of calls are made to Triple 000 every day in Australia and my job is to direct them to the service they desperately need. When you call Triple 000 the first person you’ll hear is me, or the many other call takers employed in 3 different states. You’ll hear “Emergency. Police, Fire or Ambulance?” “What state and town is the emergency in?” That’s it. It’s a simple job, but it isn’t easy. If all goes according to protocol, we connect your call to who you need, the next dispatcher will assist you from there and I will go on to take the next call. I think it’s safe to assume that not all our calls are that cut and dry. So many factors come into play when you’re dealing with someone in an emergency.

I took this job because although I loathe phone calls in general, I tend to believe I am a good person who likes to help people. I also took the job because I needed one, I needed money. I hadn’t worked in a while due to a previous workplace injury, making it almost impossible to find something I could physically do. So, this job seemed like a pretty sweet deal. I get to help people AND I get paid for it. As the months and years pass, the mental trauma that comes with the job decreases as your skin thickens. Of course, there are calls that are forever embedded in your mind. You remember the first suicide call. And the second. And the third. The suicide calls are my personal trigger. The horrific screams and pleas for help. The domestic violence calls, one after the other, the abuse you receive and the men masturbating to you on the other line. But after a certain period of time, (for me it was 6 months of crying in the training room, through boxes of tissues and cups of tea), that guard you’ve put up that emotionally separates you from the reality of these calls, eventually gives you the endurance you need to do your job in the most efficient way possible.

I also never would have gotten through those first months without incredibly supportive co-workers and supervisors who had all the time and patience in the world for me. Patience is a necessity to do this job. There are certain aspects of my life where patience hasn’t exactly been my strong suit, like when I’m driving, for example. Surprisingly though, patience came naturally.

Eventually though, I came to realise that the narrative I’d been taught about how only good people would choose to work in fields of emergency services was a lie. Or maybe that was something I foolishly told myself, that we can trust the people who are paid to keep us safe. They want to help us; otherwise, why would they do this job? That was a bitter pill for me to swallow, and to accept, that there are people I work with that don’t actually care about helping these callers. Sure, they’re going to do their job, if they didn’t do it correctly, they wouldn’t have a job anymore. But that’s all it is to some of them, a job, a paycheque. That emotional barrier that took me months of crying and pep talks to create just doesn’t need that much work for some of them, if any at all. The patience that came naturally to me, even when it was tested to the highest degree, wasn’t even present in some.

Whether it was the years of constant berating that weathered their spirits I don’t know, but it was shocking to see. I’m not exempt from letting callers get under my skin, to ending a call and needing to log out for 5 minutes to gather myself due to an endless line of people screaming at me, not answering basic questions, threatening to kill me and blaming me for delays in transfers. I’m a highly emotional person and no matter how hard I tried there would be days that it would still incite a deep-seated hatred of humans. But to do my job well I wholeheartedly believe that each new call we take should be met with the same patience, empathy and understanding that we would expect or want if it was our own emergency or an emergency of a loved one.

It took some time for me to process, I think it has been a blind spot for me, or maybe I’m just naïve but, it’s almost implausible to me that having empathy isn’t an intrinsic part of being human. I always knew that but, seeing it day in and day out for my job just really beat me over the head with it, people don’t care. What I mean by that is, they don’t give a shit about you. Even the ones that are being paid to. Maybe I should preface this with only SOME don’t give a shit. However many there are in precise numbers, I don’t know. What I know is that 1 is too many. What I also know is that when it comes to police, they come in droves.

I will say this upfront because I know I’ll get criticism for the way I speak about first responders. I have the utmost respect for all lines of emergency service workers. Those with integrity and do what they do for the right reasons. I’m not talking about them.

What’s the obsession with true crime?

I’ve been an avid true crime fan since the early 2000’s, but the interest has never worn off. If anything, it has only intensified and become more complex over time. The fascination with the mind of a killer, what makes them fundamentally different to those that don’t kill, and what may have happened in their life that contributed to the act. These are standard reasons people give when asked why true crime is interesting to them. And I’m no different.

Growing up mentally ill, and navigating adulthood the same way, I watched as my mind tried to kill me, watched as I dove headfirst into alcoholism, dousing my insides in a desperate attempt to soothe any aching, open wounds I could. I’m no stranger to a disturbed mind. But mine always told me to take my pain and anger out on myself, never someone else. So why is it so different for people that choose to kill? The ongoing “pursuit of happiness”, which most of us are burdened with, requires introspection and perception. It is natural to compare ourselves to others, so to understand myself I had a nagging need to understand others, to compare my experiences with theirs. It meant learning about the nuances of who they were.

Click on image for addiction support services in Australia

This appetite for answers, to want to understand people I believe grew into an interest in psychology, true crime, and an overarching need for social fairness and justice.

Mental illness certainly plays its part in true crime. There are countless acts through history that would leave us asking if the perpetrator is “crazy”. “How can they do that if they’re not mentally ill?” “A normal person wouldn’t do that!” And in some cases, this is true. Not guilty by diminished capacity or “by reason of insanity” as it is more widely known, is a defence for a reason. But oftentimes you will find that a lot of the most inhumane acts of violence and other antisocial crimes are committed by people you wouldn’t expect. Regular people. And in my opinion, that is far more terrifying. It means these monstrous acts of cruelty are done so not just by the misanthropic anomalies or people we wouldn’t dare associate ourselves with. They’re also committed by respectable people that are well integrated in our society and sometimes even in positions of power, prestige and privilege.

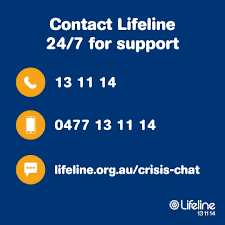

Click on image for Lifeline Australia website

To “Protect and Serve”

But what about those that are being paid to ensure our safety? To uphold the law, to enforce it, live by its standards. What happens when they’re the ones that are victimising the very people they have sworn to protect and serve?

The small taste of what my workplace gave me, while not criminal acts or even something some may deem as wrong, to me were an introduction into the system that fails us at every tiny step. The indifference and lack of empathy towards people in need was a piece of a larger issue that has sent me spinning into existential dread, resentment and hatred for humans. In my research of true crime and police corruption, it has led me to finding familial links to one of Australia’s most infamous and documented cases of New South Wales Police corruption, a brave whistleblower and her murder.

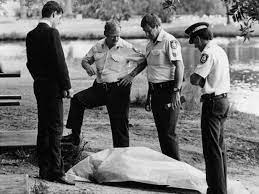

On the 7th of February 1986 at around 8:45am, a man was jogging in Centennial Park in Sydney, Australia when he saw a body floating in Busby’s Pond. He ran to the ranger’s office and spoke with the ranger on duty, Brian Calbert. Brian alerted authorities, and once Police arrived on scene Brian was accompanied by two police officers as he rowed out to retrieve the body. When a detective saw the person’s face, they exclaimed “That’s Huckstepp!”

References:

Huckstepp: A Dangerous Life – John Dale

Image of Busby’s Pond Centennial Park – https://www.centennialparklands.com.au/visit/our-parks/centennial-park/ponds/busbys-pond

Leave a comment